WISHING YOU HAD A WAND TO ABOLISH REMOTE CLASSROOMS?

HAVE COURAGE! DON'T BELIEVE THE CYNICAL NEWS ABOUT ONLINE LEARNING

Today’s Gen Z college students have grown up with technology; it’s been a main source of entertainment and communications for most of their lives. You’d imagine, then, that learning primarily online would have been a cinch for them. But what’s the reality? Has online learning actually had a negative impact on student engagement and performance? Have students rebelled at the practice?Last June, ATI sent out a survey to faculty (both ATI clients and those who don’t use ATI solutions) to ask about the impact of the pandemic. What were educators’ and administrators’ expectations going into the fall semester? What were their concerns? What changes had they made — or planned to make?

As the abridged fall semester nears its conclusion, we’ve gathered answers based on our research as well as looking at other resources.

If your students have been doing well, congratulations! Let us know in the comments how you’ve been succeeding. If, however, you’ve been struggling with getting your students engaged, you’ll hopefully discover some ideas to make your teaching even more effective.

WHAT’S SO NEGATIVE ABOUT ONLINE-ONLY LEARNING?

WHAT’S SO NEGATIVE ABOUT ONLINE-ONLY LEARNING?

In March 2020, just after many campuses shifted all courses to fully online environments, Educause Review published research (conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic) about educators’ perspectives regarding online learning.

“Despite overwhelming empirical evidence demonstrating the efficacy of online learning,” Educause Review stated, “only 21% of faculty agree that online learning can help students learn effectively.”

The following month — after the real-life necessity of moving online had occurred — EducationData.org published statistics showing administrators similarly lacked faith in any positive benefits of the method. In that survey, college and university presidents’ top concerns, from greatest to least, included:

- Maintaining student engagement (cited by 81% of respondents)

- Training faculty less familiar with teaching online (75%)

- Ensuring student access (69%)

- Ensuring high academic standards (50%)

- Availability of technology (50%)

- Faculty buy-in (22%).

Respondents to ATI’s survey in June had similar worries. Specifically, when asked about replacing clinical hours with simulation, 73% said their biggest anxiety was delivering a quality education. Others were concerned about how they would keep students engaged in an online-only environment.

RESEARCH REPORTS ON THE REALITIES

What’s been the reality since the pandemic began? Inside Higher Ed hosted a webcast on July 1, 2020, reporting the results of a poll conducted with university presidents in mid-June.

The respondents’ assessment of remote learning revealed some positive statistics. High percentages of respondents replied they felt extremely or very successful in the areas of:

The respondents’ assessment of remote learning revealed some positive statistics. High percentages of respondents replied they felt extremely or very successful in the areas of:

- Making tech support available (81%)

- Achieving faculty buy-in (73%)

- Ensuring high academic standards (55%)

- Providing tutoring/student support (53%).

Their levels of confidence going into the Fall 2020 semester were also high. Respondents said they were very or extremely confident about:

- Providing a flexible, high-quality learning experience (66%)

- Giving remote students a high-quality learning experience (57%)

- Ensuring the safety of faculty members (56%)

- Giving remote students high-quality support and services (55%).

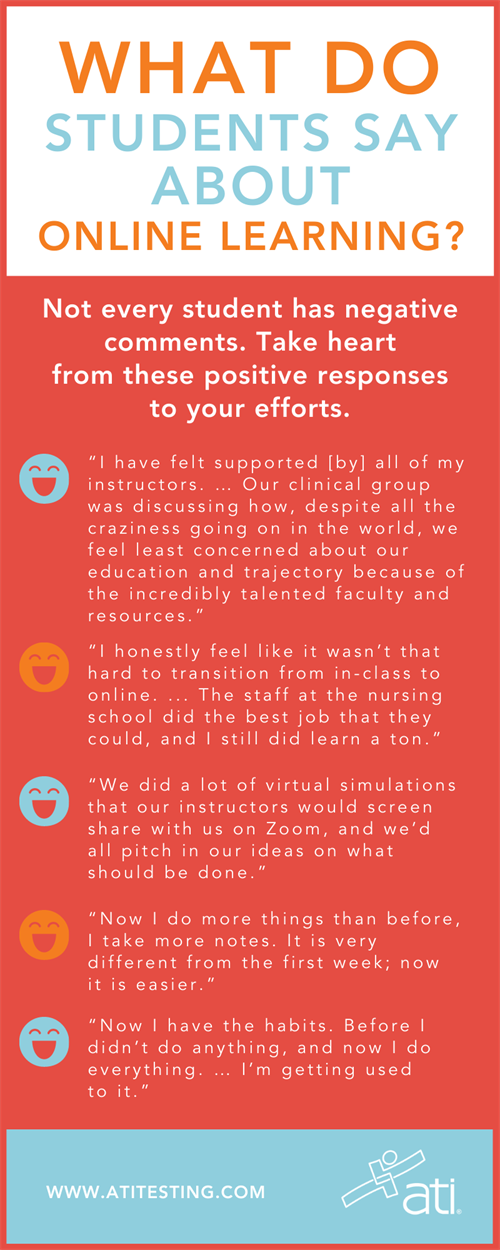

Students appeared to be adjusting, too. In a study of nursing students in Spain (published in the "International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health"), students initially experienced 2 well-differentiated phases. During the first “shock” phase, students faced “disorientation.” But, after about 7 to 10 days, students entered a normalization period. During this stage, comments from students included:

- “Now I do more things than before, I take more notes. It is very different from the first week; now it is easier.”

- “Now I have the habits. Before I didn’t do anything, and now I do everything. … I’m getting used to it.”

Unfortunately, negative experiences did abound, particularly in reviewing the open-ended responses to ATI’s survey and especially in regard to anxiety.

ATI’s survey noted that respondents’ institutions anticipated that student well-being would be a concern, and most administrators reported being proactive in addressing it. 76% said they planned to send communications specifically aimed at reducing potential anxiety about changes due to COVID-19.

Nevertheless, among the more than 500 open-ended answers, respondents said students were most concerned about:

- Missing clinicals

- Catching COVID-19

- Dissatisfaction with online learning.

DOWNLOAD THE INFOGRAPHIC AT RIGHT AS A HANDY REFERENCE

One educator at a BSN program in the West lamented, “How will we support/engage clinical experiences and hands-on learning? [How will we] convert to fully online learning for all theory and some aspects of lab and clinical? Most [students] want some face-to-face contact with faculty and peers.”

She also noted concerns about scheduling. “Our students are post-traditional, have jobs, kids, spouses, and other life commitments to balance with academic priorities, sharing computers, helping kids with homeschooling and, perhaps, picking up extra hours at work. [All] will be a significant concern.”

Predicting that her PN program would engage a hybrid approach, another faculty member in the West stated that students had expressed not wanting to “teach themselves.” (Most, she noted, were anticipating an increased responsibility in reading and preparing for online instruction.)

Students of a BSN educator in the Northeast had similar worries. “Most do not care for 100% online learning; face-to-face is preferred overwhelmingly. So, there is anxiety R/T the amount online,” she wrote.

Other comments noting concerns about online instruction included:

- “Keeping engaged with the students and meeting their individual learning needs.” — BSN program, Southern U.S.

- “Keeping students honest and engaged. Making sure they are learning the content.” — PN program, Great Lakes region

- “Controlling the class environment; maintaining everyone’s focus on learning and being able to watch progress.” — BSN program, Northeastern U.S.

Backing up educators’ concerns was research detailed in the Inside Higher Ed webinar. It cited smaller percentages of respondents identifying remote learning as extremely or very successful as it related to:

- Training less-experienced faculty (47%)

- Ensuring equitable access for students (45%)

- Maintaining student engagement (31%)

- Promoting student well-being (17%).

POSITIVE OUTCOMES AND OUTLOOKS

POSITIVE OUTCOMES AND OUTLOOKS

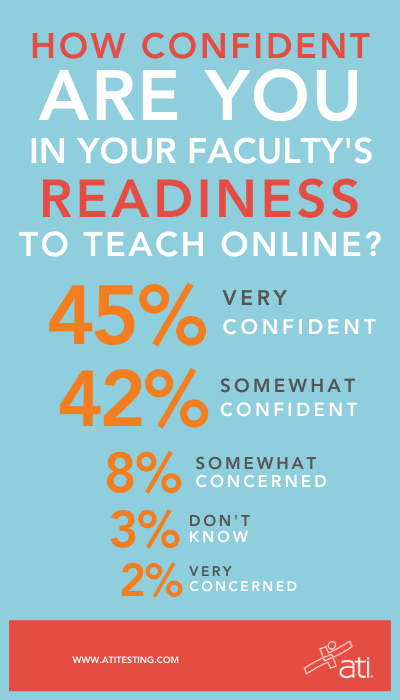

While educators’ concerns were frequent disclosed in ATI’s survey results, respondents did reveal some positive expectations. One survey question revealed an especially optimistic answer regarding respondents and their peers’ abilities to teach successfully online.

45% of ATI respondents said they were very confident in faculty’s readiness, and 42% said they were somewhat confident. Only 3% said they didn’t know about their faculty’s readiness, 8% said they were somewhat concerned, and 2% said they were very concerned.

ATI’s survey, as well as other online sources, reported other positive outcomes related to online learning since the start of the pandemic:

- Increased enrollment. “Faculty are comfortable teaching online, and students adapted well,” wrote an Illinois administrator in ATI’s survey. “They wanted to be on the front line. Parents were begging for clinical exposure. Applications have skyrocketed, and enrollments have only gone up.”

- Impressed students. Faculty at Vanderbilt University created virtual clinical simulations for students to remotely instruct educators in the sim lab, allowing the same competency assessments as in clinicals. In describing the experience, one educator said: “Students are amazed that we created these things. They’ve had great experiences — it’s been intense and challenging — and they’ve had good teamwork.” Positive comments from students included: “I have felt supported [by] all of my instructors in the past weeks. … Earlier this week, our clinical group was discussing how, despite all the craziness going on in the world, we feel least concerned about our education and trajectory because of the incredibly talented faculty and resources at VUSN.”

DOWNLOAD THE INFOGRAPHIC ABOVE AS A HANDY REFERENCE

- Positive experiences. Michigan State University nursing students learned how to perform head-to-toe assessments on Zoom. A student said, “I honestly feel like it wasn’t that hard to transition from in-class to online. ... The staff at the nursing school did the best job that they could, and I still did learn a ton.” Another said: “We did a lot of virtual simulations that our instructors would screen share with us on Zoom, and we’d all pitch in our ideas on what should be done.”

- Unexpected advantages. Research in “Nurse Education in Practice” revealed that online learning offered an advantage over in-person learning by facilitating “parallel delivery of theory and practice,” rather than serial delivery. The article also countered concerns of prolonged student isolation by “facilitating synchronous application of taught e-clinical skills within the practice learning environment and increasing timetabling flexibility.”

- Surprising assists. 71% of respondents to a survey published in “Anatomical Sciences Education” said the sudden transition to online learning offered the benefit of developing new online resources. 21% of respondents said a benefit was “upskilling in new technologies and resources.” 50% cited benefits of academic collaboration. 29% noted the benefit of working remotely. And 14% saw the benefit of “incorporation of blended learning in future curriculum development.”

- Post-pandemic paybacks. “During [the] COVID-19 crisis, the preclinical phase of medical curricula has successfully introduced the novel culture of ‘online home learning’ using technology-oriented innovations, which may extend to [the] post-COVID era to maintain teaching and learning in medical education,” noted an article in “Comprehensive Clinical Medication.“ The use of emergent technology (e.g., artificial intelligence for adaptive learning, virtual simulation, and telehealth) for education is most likely to be indispensable components of the transformative change and post-COVID medical education.”